Andrzej Jerzy Wrona, Dominik Chodor, lek Jarosław Zgajewski, lek Michał Piotrowski

Żródło: „Przegląd Urologiczny”, 2019, nr 118.

Currently, the gold standard treatment for patients with muscle-invasive bladder cancer is radical cystectomy. Patients undergoing radical cystectomy require simultaneous reconstruction of the urinary tract. Among the methods of urinary diversion, we can mention uretero-cutaneous conduits, orthotopic neobladder, internal continent intestinal reservoirs, and non-continent diversions, among which the ileal conduit predominates.

One of the most commonly performed methods of urinary diversion is the ileal conduit. There are two main types of uretero-ileal anastomoses: the Bricker technique and the Wallace technique. The Bricker technique involves spatulating the ureters and individually suturing each ureter to the side of the ileal conduit. In the Wallace technique, there are two types. In Type I, the ureters are incised, placed parallel to each other, and sutured along their inner edges. These joined ureters are then sutured to the proximal end of the ileal conduit. In Type II, the incised ureters are sutured so that the distal end of one ureter is sutured to the apex of the incision of the second ureter, and then, as in Type I, joined to the proximal end of the ileal conduit.

One of the complications of urinary diversion through an ileal conduit is the narrowing of the uretero-ileal anastomosis. This narrowing is usually asymptomatic and can lead to hydronephrosis, deterioration of kidney function, urinary tract infections, and ultimately kidney loss. Various treatment methods for uretero-ileal anastomotic strictures are described. The most commonly performed procedure is open surgery to excise the stricture and perform a re-anastomosis of the ureters to the ileal conduit

The procedure can also be performed laparoscopically or with robot assistance. Alternative treatments include endoscopic techniques such as balloon dilation of the stricture, endoscopic incision of the stricture, or placement of a DJ stent. In cases where no treatment is feasible, patients may require permanent percutaneous nephrostomy to preserve kidney function. The aim of this article is to present a new method for treating uretero-ileal anastomotic strictures using the Detour device (pyelovesical bypass)

The structure of the Detour prosthesis and the description of the procedure

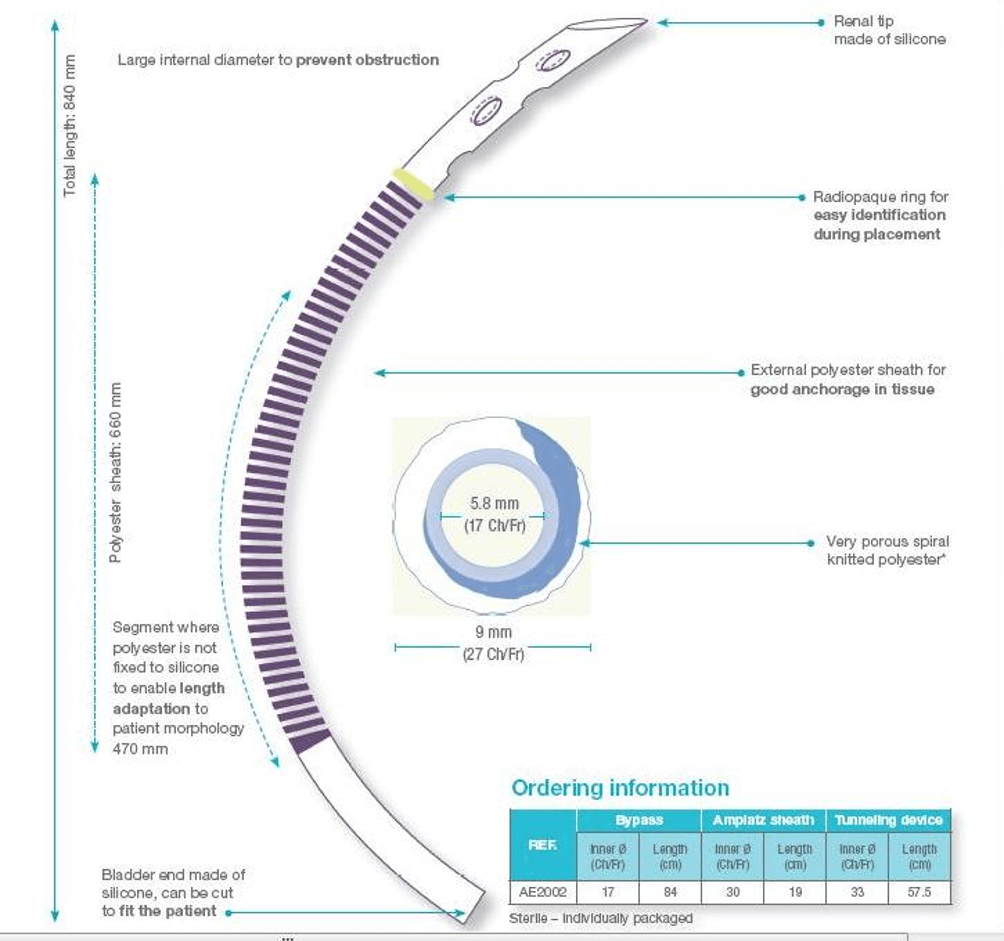

The Detour prosthesis consists of an outer tube made of polytetrafluoroethylene (PTFE) sized 27F and an inner silicone tube sized 17F. The inner tube protrudes beyond the outer part at each end. At the junction of the inner and outer parts of the renal end of the prosthesis, there is a radiopaque ring that marks the correct position of the prosthesis in the kidney (Figure 1).

Figure 1: The structure of the Detour prosthesis (Used with permission from Coloplast, Inc.)

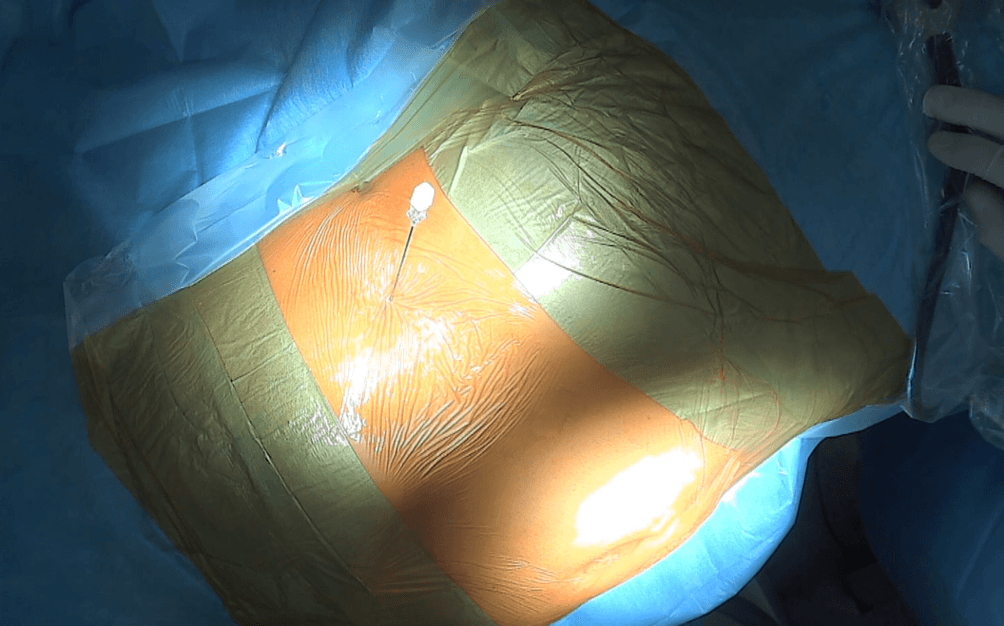

The procedure is performed under general anesthesia. The patient is positioned on their side with the pelvis slightly rotated to facilitate easy access to both the lumbar area and the urostomy. Then, the table is partially folded to elevate the patient’s side. The puncture into the kidney is performed under ultrasound and X‑ray guidance slightly to the side to avoid kinking of the Detour prosthesis where it exits the kidney and directs towards the urostomy (Fig. 2).

Figure 2: The needle is introduced into the left kidney collecting system. Frontal view of the patient. The patient is lying on their right side, with the head turned towards the left side, the umbilicus visible at the bottom of the image (urostomy not visible).

Figure 2: The needle is introduced into the left kidney collecting system. Frontal view of the patient. The patient is lying on their right side, with the head turned towards the left side, the umbilicus visible at the bottom of the image (urostomy not visible).

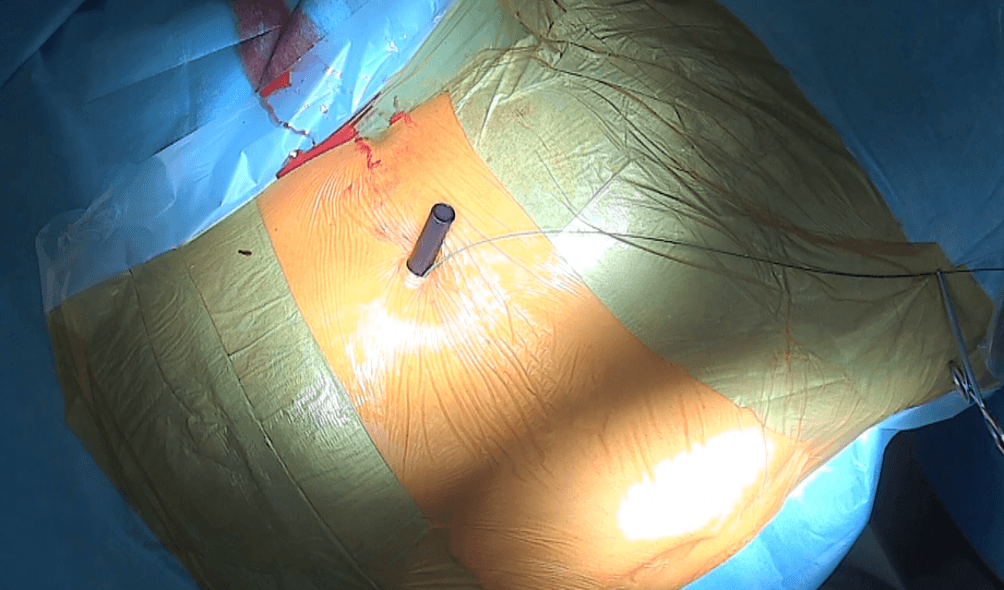

The Detour prosthesis is introduced into the kidney through the Amplatz sheath under fluoroscopic guidance (Fig. 3).

Figure 3: Access to the left kidney’s UPJ is created — the Amplatz sheath 30F is visible, with the safety wire to its right.

Figure 3: Access to the left kidney’s UPJ is created — the Amplatz sheath 30F is visible, with the safety wire to its right.

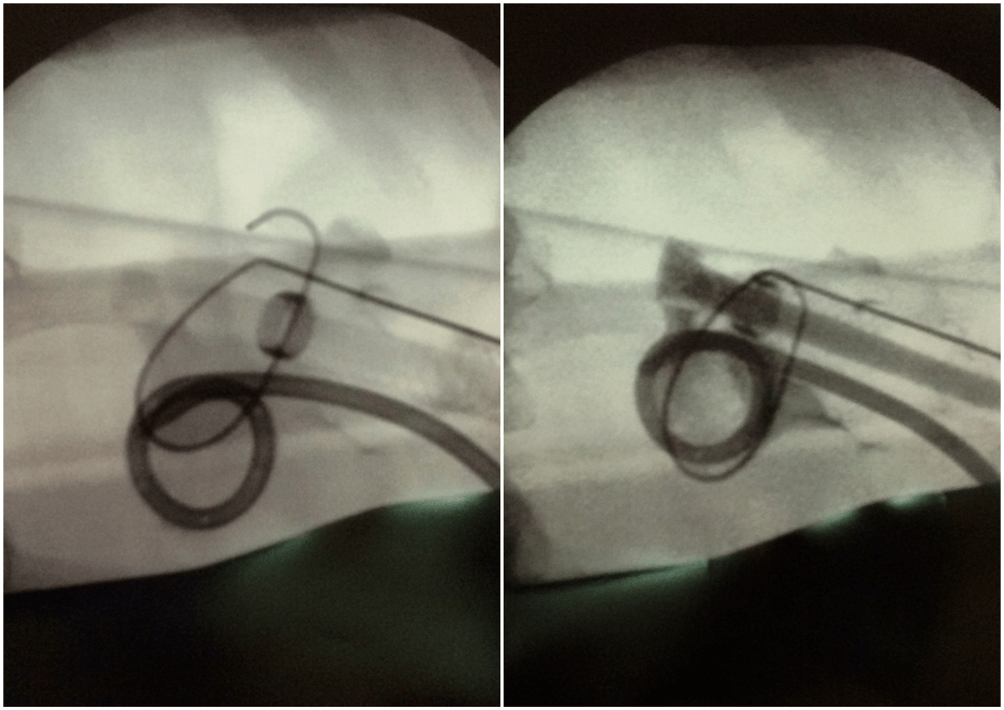

The radiopaque marker at the proximal end of the prosthesis helps stabilize its position so that the PTFE sheath is enveloped by the kidney parenchyma and does not intrude into the UPJ, preventing encrustations, while the kidney parenchyma stabilizes the prosthesis.

Figure 4: Intraoperative X‑ray images during the prosthesis implantation procedure — on the left, the Detour prosthesis is visible above the nephrostomy drain. The radiopaque ring (arrow) marking the position of the boundary point between the internal and external parts of the renal end of the prosthesis is visible. On the right, the moment of contrast administration through the prosthesis — the contrasted lumen of the prosthesis (17F) is visible, marked by an arrow.

Figure 4: Intraoperative X‑ray images during the prosthesis implantation procedure — on the left, the Detour prosthesis is visible above the nephrostomy drain. The radiopaque ring (arrow) marking the position of the boundary point between the internal and external parts of the renal end of the prosthesis is visible. On the right, the moment of contrast administration through the prosthesis — the contrasted lumen of the prosthesis (17F) is visible, marked by an arrow.

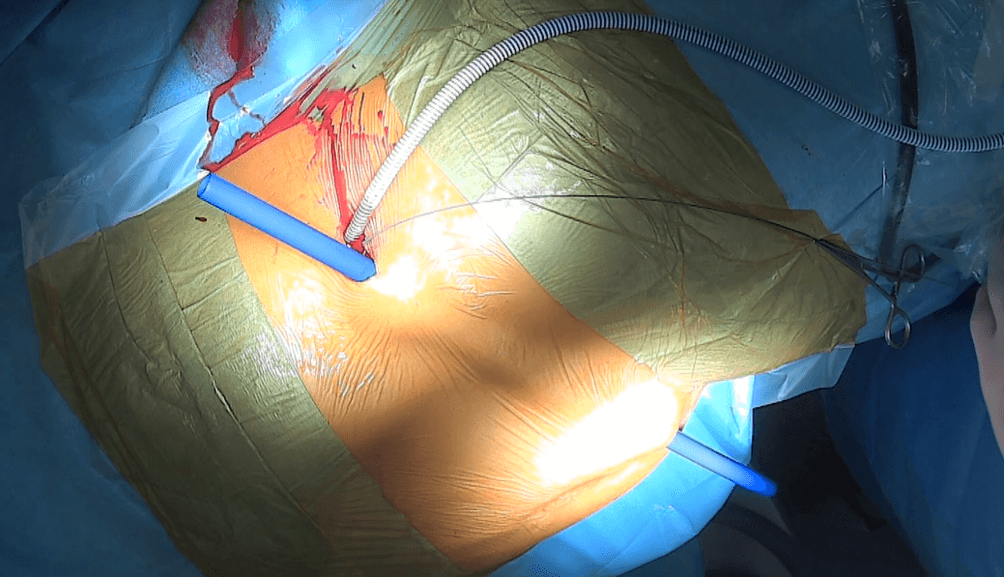

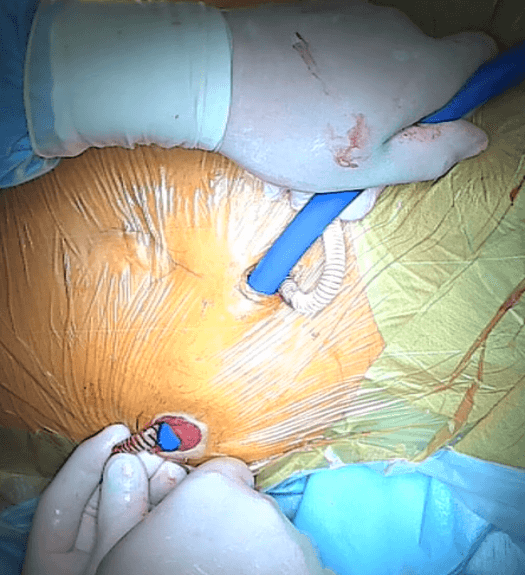

Once the prosthesis is correctly positioned, we remove the Amplatz sheath. The Detour prosthesis is then passed subcutaneously. To create a tunnel for the prosthesis from the lumbar region to the para-ostomy area, we use a plastic tube of appropriate width (see figure 5).

Figure 5: Detour prosthesis (27F) inserted into the right kidney. Creation of a subcutaneous channel for the Detour prosthesis – a blue plastic tube is visible passing through the incision previously made in the left lumbar region, subcutaneous tissue, and exiting through an incision a few centimeters below and to the right of the umbilicus.

Figure 5: Detour prosthesis (27F) inserted into the right kidney. Creation of a subcutaneous channel for the Detour prosthesis – a blue plastic tube is visible passing through the incision previously made in the left lumbar region, subcutaneous tissue, and exiting through an incision a few centimeters below and to the right of the umbilicus.

In the case of inserting the prosthesis into the left kidney, due to the considerable distance between the left lumbar region and the urostomy located on the right side, as well as the significant curvature of the subcutaneous tract, the insertion of the prosthesis under the skin is performed in two stages. First, the prosthesis is guided to the anterior surface of the abdominal cavity, where a skin incision is made and the prosthesis is brought out through this incision (Fig. 6, Fig. 7).

Figure 6::The Detour prosthesis (27F) passed through the subcutaneous tissue.

Figure 6::The Detour prosthesis (27F) passed through the subcutaneous tissue.

.png)

Figure 7: The image was taken from a different angle from the front of the patient. The patient’s head is positioned on the left side. At the top of the image, a dressing is visible applied to the wound in the left lumbar region. The Detour prosthesis can be seen emerging from the incision located below the navel. At the bottom, the urostomy is visible.

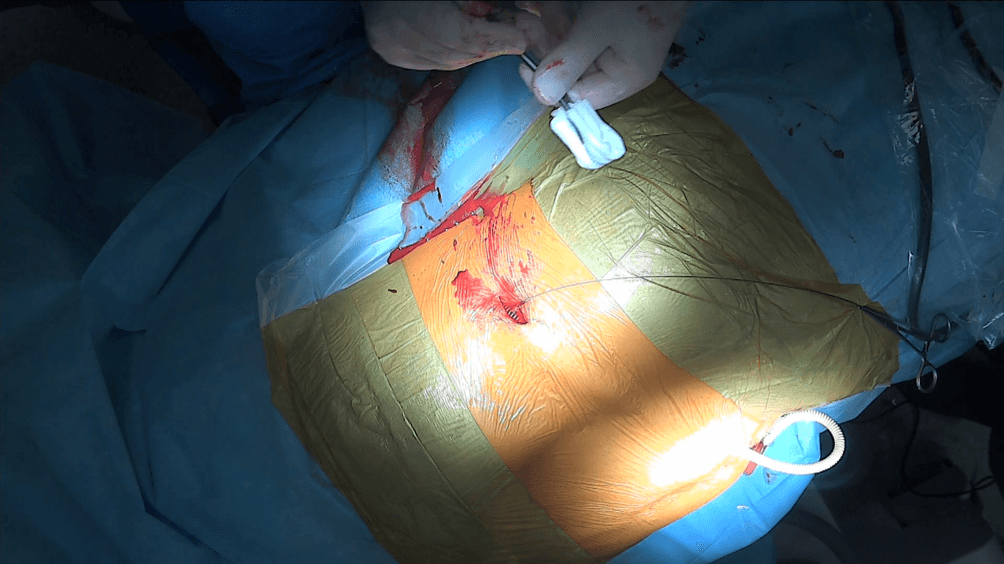

A subcutaneous channel is then created from the indirect incision reaching the lateral wall of the urostomy in its suprafascial part (Fig.8).

Figure 8: Creating a subcutaneous channel for the Detour prosthesis blindly using a finger. Next to the finger, the prosthesis inserted into the left kidney, which is yet to be implanted into the urostomy, is visible. The distal end of the Detour prosthesis, previously inserted into the right kidney during another procedure, is protruding from the urostomy..

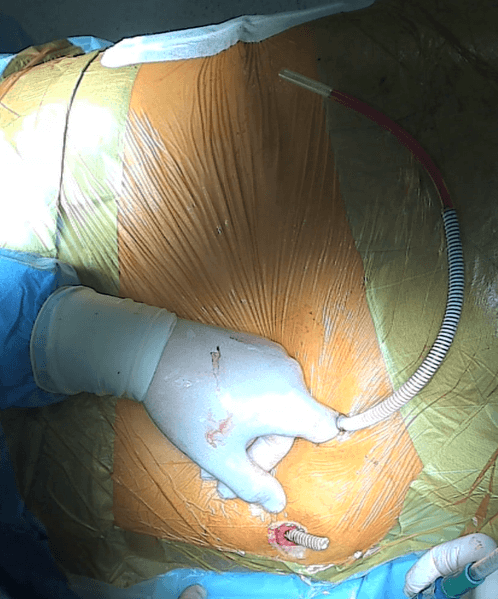

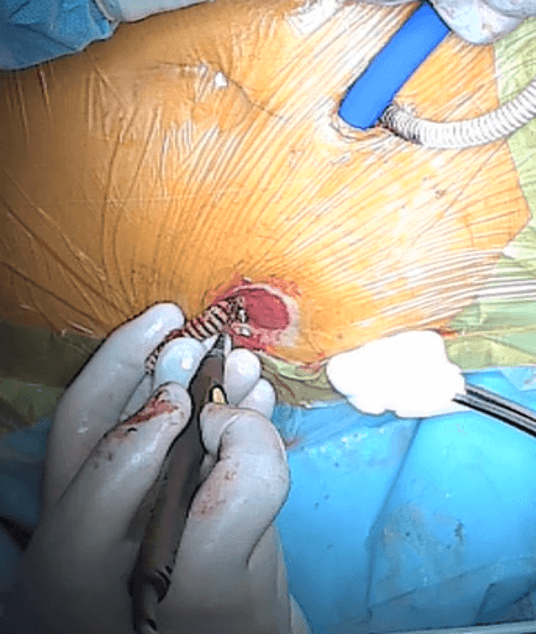

Next, the wall of the intestine is incised from the inside, and a plastic tube is passed through the incision, through which the Detour prosthesis will be conducted (Fig. 9).

Figure 9: Moment of incising the mucosa of the intestinal stoma.

Figure 10:The moment of introducing the plastic tube into the intestinal stoma.

The distal part of the prosthesis is trimmed to the appropriate length, and the external PTFE coating is sutured to the intestinal mucosa.

Figure 11: Left Detour prosthesis (27F) introduced into the intestinal stoma requires further shortening and stitching to the wall of the stoma. Beside it, the distal end of the right prosthesis is visible.

After the procedure, a Foley catheter is inserted into the intestinal stoma.

Case description.

The 72-year-old patient underwent radical cystoprostatectomy with urinary diversion through an intestinal conduit in April 2016. Following the procedure, he was hospitalized twice due to severe sepsis, once in May and once in June 2016. In July 2016, ultrasonography revealed dilatation of the right-sided renal pelvis and calyces up to the third degree. In September 2016, the patient underwent percutaneous nephrostomy of the right kidney.

Descending pyelography was performed, revealing no contrast penetration into the intestinal conduit. In October 2016, an endoscopy of the intestinal conduit was performed in an attempt to relieve the stricture of the right-sided ureterointestinal anastomosis. Due to the lack of improvement following the procedure, the patient remained with a right-sided nephrostomy. Subsequently, the patient was observed to have anemia, exacerbated carbohydrate metabolism disorders, and biochemical signs of renal insufficiency.

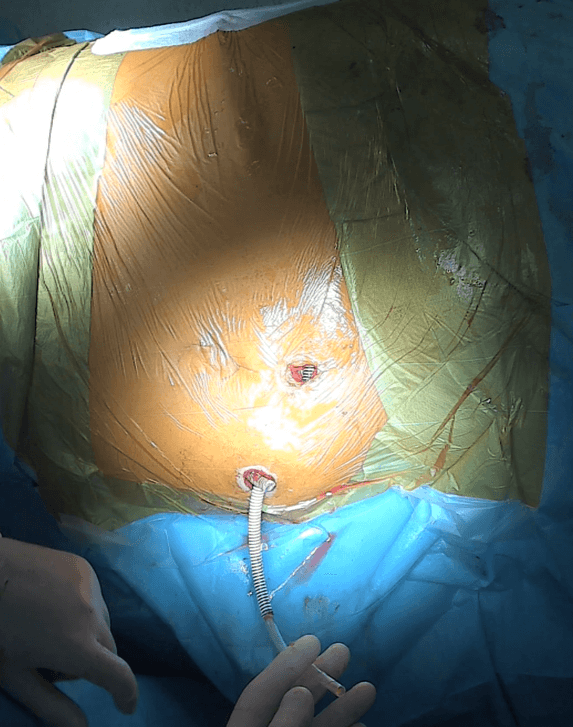

In November 2017, ultrasound revealed dilation of the left renal pelvis. In March 2018, the patient was hospitalized due to a urinary tract infection accompanied by fever. Subsequently, in April 2018, a left-sided percutaneous nephrostomy was performed. The patient was admitted to our department in October 2018. He was scheduled for implantation of a Detour prosthesis into the right intestinal conduit. The preoperative creatinine level was 151umol/L, with an eGFR of 43ml/min/1.73m^2. On October 10, 2018, under general anesthesia, the procedure of implanting the Detour prosthesis into the right kidney and intestinal conduit was performed. The duration of the surgery was 60 minutes. There were no intraoperative or early postoperative complications. Renal function parameters after the procedure remained similar to those before the surgery. Descending pyelography was performed, demonstrating normal contrast flow through the prosthesis.

Figure 12: Right-sided descending pyelography through the established nephrostomy — visible contrast enhancement of the right renal pelvis and the Detour prosthesis.

Figure 12: Right-sided descending pyelography through the established nephrostomy — visible contrast enhancement of the right renal pelvis and the Detour prosthesis.

W 7. dobie od zabiegu operacyjnego usunięto nefrostomię z nerki prawej. W 9. dobie pooperacyjnej chory został wypisany do domu. W styczniu 2019 roku chory był hospitalizowany w innym ośrodku z powodu infekcji układu moczowego z towarzyszącą gorączką spowodowaną zagięciem się końcówki protezy Detour znajdującej się we wstawce jelitowej i jej zatkaniem przez czop śluzowy. Po udrożnieniu protezy uzyskano prawidłowy pasaż moczu z nerki prawej.

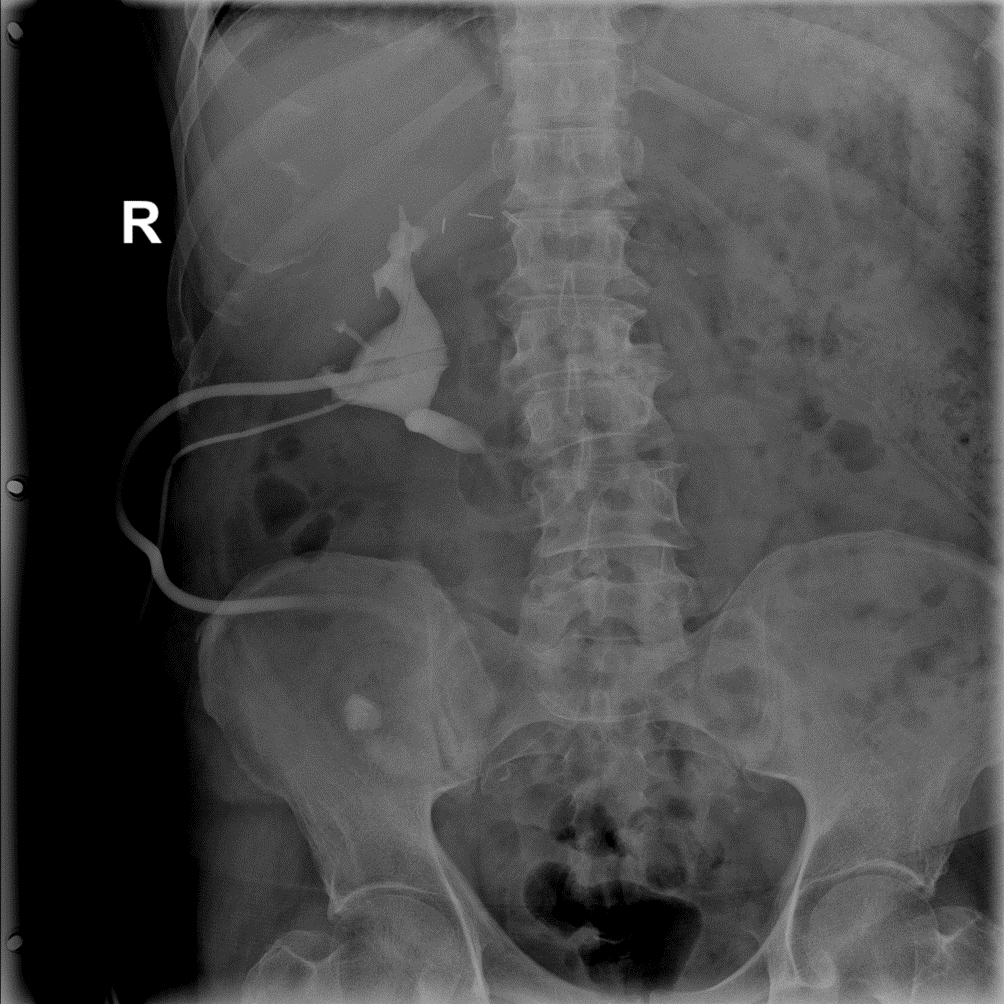

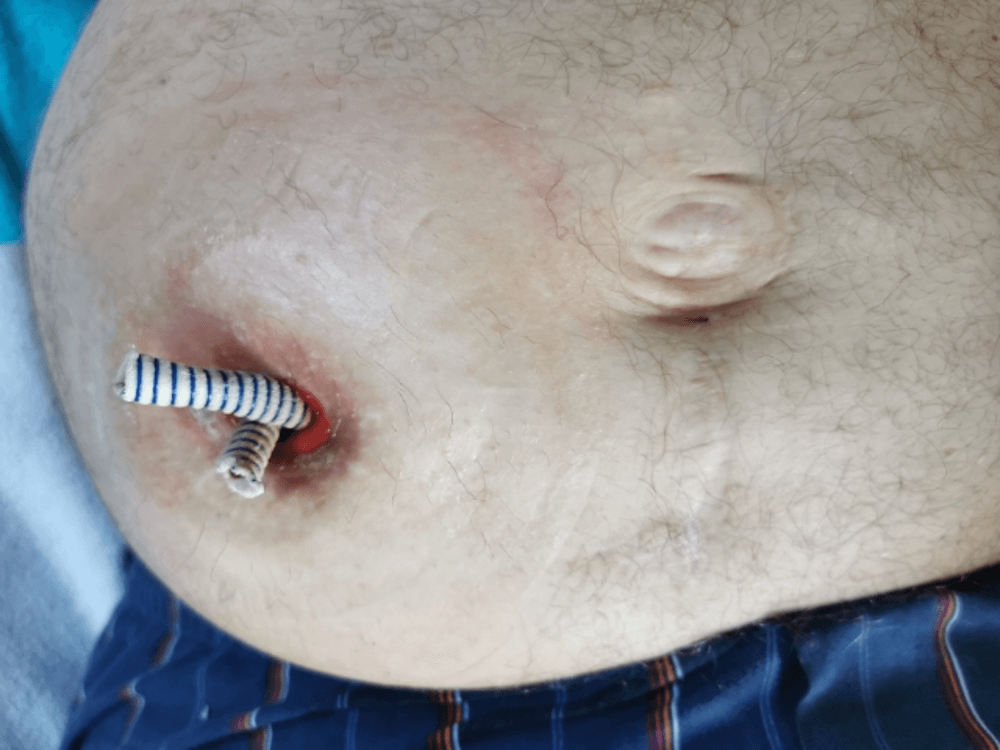

In April 2019, the patient was again scheduled for admission to the Urology Department of this hospital. During the preoperative period, the patient was treated with antibiotics due to urinary tract infection (Enterococcus faecalis). On April 2019, under general anesthesia, the procedure of implanting the Detour prosthesis into the left kidney and the intestinal stoma was performed. The duration of the procedure was 60 minutes. There were no intraoperative or early postoperative complications. Due to limited space within the intestinal stoma and the risk of prosthesis bending and obstruction by intestinal mucus, the tip of both Detour prostheses was positioned to slightly protrude through the urostomy to the outside (Figure 13, Figure 14).

Figure 13: The Detour prostheses protruded outside the stoma for better urine passage. The image was taken before attaching the urostomy bag plate.

Figure 13: The Detour prostheses protruded outside the stoma for better urine passage. The image was taken before attaching the urostomy bag plate.

Figure 14: The Detour prostheses protruded outside the stoma for better urine passage. The view after attaching the plate.

Figure 14: The Detour prostheses protruded outside the stoma for better urine passage. The view after attaching the plate.

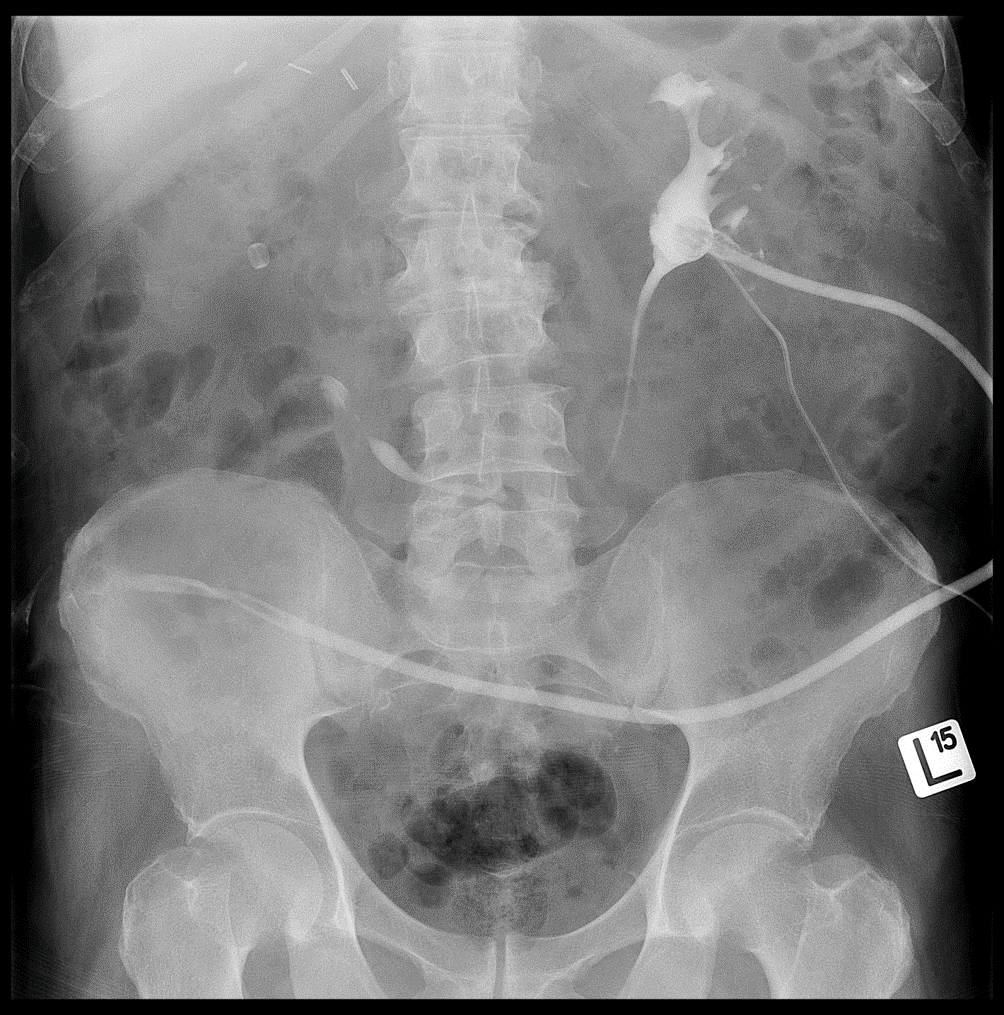

After the procedure, a descending pyelography was performed, revealing the proper flow of contrast through the prosthesis (Fig. 15).

Figure 15: Descending pyelography on the left side through the placed nephrostomy — visible contrast enhancement of the left kidney’s collecting system and the Detour prosthesis. In the projection of the right kidney, the radiopaque ring of the right Detour prosthesis is visible.

Figure 15: Descending pyelography on the left side through the placed nephrostomy — visible contrast enhancement of the left kidney’s collecting system and the Detour prosthesis. In the projection of the right kidney, the radiopaque ring of the right Detour prosthesis is visible.

On the 5th day after the surgery, the nephrostomy from the left kidney was removed. On the 7th day post-surgery, the patient was discharged home. No complications were observed postoperatively. Currently, the patient feels well, and the prostheses drain urine properly.

Summary

Up to now, the implantation of an artificial ureter has been performed in cases of obstructive uropathy with obstruction occurring at the level of the ureter. The Detour prosthesis has been used in patients with both malignant and benign causes of ureteral obstruction. There are also reports in the literature of cases where this method was used in patients after kidney transplantation. Constriction of the uretero-intestinal anastomosis in patients undergoing radical cystectomy with urine diversion through an intestinal conduit may be another indication for the use of the Detour prosthesis.

In patients for whom other methods have failed or for whom other treatment options are not feasible, percutaneous nephrostomy remains the method of urine diversion. However, percutaneous nephrostomy is associated with a decreased quality of life for patients and is not free from complications. The implantation of the Detour prosthesis can be successfully used in these patients. The procedure itself is not complicated, and an additional advantage is the minimally invasive nature of the surgery. Implantation of an artificial ureter carries the risk of both early and late complications, so patients require careful observation in the postoperative period and during subsequent follow-up.

Early-diagnosed complications can be adequately managed [14, 21, 22]. Due to the experimental nature of this procedure, more research and a longer observation period are needed to fully assess its long-term effectiveness. Nevertheless, the implantation of an artificial ureter in the patient described in this article significantly improved his quality of life and allowed for normal functioning while maintaining satisfactory kidney function. We hope that the use of kidney drainage with the Detour prosthesis will become an increasingly preferred treatment method for patients with ureteroenteric anastomotic strictures following radical cystectomy.

dr n med. Andrzej Jerzy Wrona

Szpital Specjalistyczny im. Edmunda Biernackiego w Mielcu

kierownik Oddziału Urologii: dr n. med. Andrzej Jerzy Wrona

lekarz Dominik Chodor

Szpital Specjalistyczny im. Edmunda Biernackiego w Mielcu

kierownik Oddziału Urologii: dr n. med. Andrzej Jerzy Wrona

lekarz Jarosław Zgajewski

Szpital Specjalistyczny im. Edmunda Biernackiego w Mielcu

kierownik Oddziału Urologii: dr n. med. Andrzej Jerzy Wrona

lekarz Michał Piotrowski

Wojewódzki Specjalistyczny Szpital im. M. Pirogowa w Łodzi. Pracownia RTG i TK.

kierownik pracowni: dr n. med. Janusz Ścibór

Bibliography

- Campbell-Walsh, et al. Urology. 10th ed. International Edition. 2012. Elsevier.

- Weiguo Hu, Boxing Su, Bo Xiao, Xin Zhang, Song Chen, Yuzhe Tang, Yubao Liu, Meng Fu and Jianxing Li, Simultaneous antegrade and retrograde endoscopic treatment of non-malignant ureterointestinal anastomotic strictures following urinary diversion, BMC Urology (2017) 17:61 DOI 10.1186/s12894-017‑0252‑0

- Niall F. Davis, MD; John P. Burke, MD; TED McDermott, MD; Robert Flynn, MD; Rustom P. Manecksha, MD; John A. Thornhill, MD, Bricker versus Wallace anastomosis: A metaanalysis of ureteroenteric stricture rates after ileal conduit urinary diversion Can Urol Assoc J 2015;9(5–6):E284-90. http://dx.doi.org/10.5489/cuaj.2692

- Yam W.L. , Lim S.K.T. , Teo J.K. , Ng K.S. , Ng F.C. , Balloon dilatation of ureteric and ureteroileal strictures, Eur Urol Suppl 2016;15(3);e130

- Sero Andonian, Kevin C. Zorn, Steven Paraskevas and Maurice Anidjar, Artificial Ureters in Renal Transplantation, Urology 66: 1109.e9–1109.e11, 2005

- Xiao-Dong Jin a,b,1, Simone Roethlisberger c,1, Fiona C. Burkhard a, Fre´de´ric Birkhaeuser a, Harriet C. Thoeny d, Urs E. Studer a,Long-term Renal Function After Urinary Diversion by Ileal Conduit or Orthotopic Ileal Bladder Substitution, European Urology 61 (2012) 491–497

- Antonio Rosales, Esteban Emiliani *, Josep T. Salvador, Juan Antonio Pen˜a, Josep M. Gaya,

Joan Palou, Humberto Villavicencio, Laparoscopic Management of Ureteroileal Anastomosis Strictures :

Initial Experience, European Urology 70 (2016) 493–498 - Moschonas D., Soares R., Swinn M., Woodhams S., Mostafid H., Menezes P., Perry M., Patil K., Endoscopic management versus robotic repair of ureteroileal anastomosis strictures after robotic assisted radical cystectomy and ileal conduit formation, Eur Urol Suppl 2016; 15(7):229

- Ballestero Diego R. , Campos F. , Zubillaga Guerrero S. , Velilla Diez G. , Herrero Blanco E. , Calleja Hermosa P., Varea Malo R. ‚Correas Gomez M.A. , Portillo Martin J.A. , Gutierrez Baños J.L. Robot-assisted management for ureteroileal stricture. Description of our technique, Eur Urol Suppl 2017; 16(6);e2457

- Harrech YE, Ghoundale O, Touiti D (2017) Percutaneous Ureteral Dilations for Management of Uretero-Intestinal Anastomosis Stricture following Bricker Urinary Diversion. Urol Nephrol Open Access J 5(3): 00170. DOI: 10.15406/unoaj.2017.05.00170

- Francois Desgrandchamps, Pascal Paulhac, Sophie Forrnairon, Eric De Kerwller, Alain Duboust, Pierre Teillac and Alain Le Duc, Artificial Ureteral Replacement for Ureteral Necrosis after Renal Transplantation: Report of 3 Cases, The Journal of Urology Vol. 159,1830–1832, June 1998

- Haddad N, Andonian S, Anidjar M, Simultaneous bilateral subcutaneous pyelovesical bypass as a salvage procedure in refractory retroperitoneal fibrosis. Can Urol Assoc J 2013;7(5–6):e417-20.http://dx.doi.org/10.5489/cuaj.1395

- Jurczok A, Loertzer H, Wagner S, Fornara P. Subcutaneous nephrovescical and nephrocutaneousbypass: palliative approach to ureteral obstruction caused by pelvic malignancy. Gynecol Obstet Invest 2005;59:144–8. http://dx.doi.org/10.1159/000083088

- Lloyd SN, Tirukonda P, Biyani CS, Wah TM, Irving HC. The detour extra-anatomic stent‑a permanent solution for benign and malignant ureteric obstruction? Eur Urol. 2007 Jul;52(1):193–8. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.eururo.2006.11.008

- Muller CO, Meria P, Desgrandchamps F. Long-term outcome of subcutaneous pyelovesical bypass in extended ureteral stricture after renal transplantation. J Endourol. 2011 Aug;25(8):1389–92. http://dx.doi.org/10.1089/end.2011.0085

- Yazdani M, Gharaati MR, Zargham M. Subcutaneous Nephrovesical Bypass in Kidney Transplanted Patients. Int J Organ Transplant Med. 2010; 1(3): 121–124.

- Azhar RA, Hassanain M, Aljiffry M et al. Successful salvage of kidney allografts threatened by ureteral stricture using pyelovesical bypass. Am J Transplant. 2010 Jun;10(6):1414–9. http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/j.1600–6143.2010.03137.x

- Ahmad I, Pansota MS, Tariq M, et al. Comparison Between Double J (DJ) Ureteral Stenting and Percutaneous Nephrostomy (PCN) in Obstructive Uropathy. Pak J Med Sci 2013;29(3):725–729. http://dx.doi.org/10.12669/pjms.293.3563

- Hsu L, Li H, Pucheril D, Hansen M, Littleton R, Peabody J, Sammon J . Use of percutaneous nephrostomy and ureteral stenting In management of ureteral obstruction. World J Nephrol 2016 March 6; 5(2): 172–181

- Haddad N, Andonian S, Anidjar M, Simultaneous bilateral subcutaneous pyelovesical bypass as a salvage procedure in refractory retroperitoneal fibrosis. Can Urol Assoc J 2013;7(5–6):e417-20. Page 4/6 http://dx.doi.org/10.5489/cuaj.1395

- Andrzej Jerzy Wrona, Jarosław Zgajewski, Norbert Kopeć, Dominik Chodor, Paweł Kopcza, Stefan Klekot, Subcutaneous pyelovesical bypass – Detour bypass – as a solution for ureteric obstruction, Cent European J Urol. 2017; 70(4): 429–433. doi: 10.5173/ceju.2017.1397

More information about zestawu Detour.

Polski

Polski